Menace to Your Gut Flora: Understanding C.Diff and How it Affects Your Microbiome

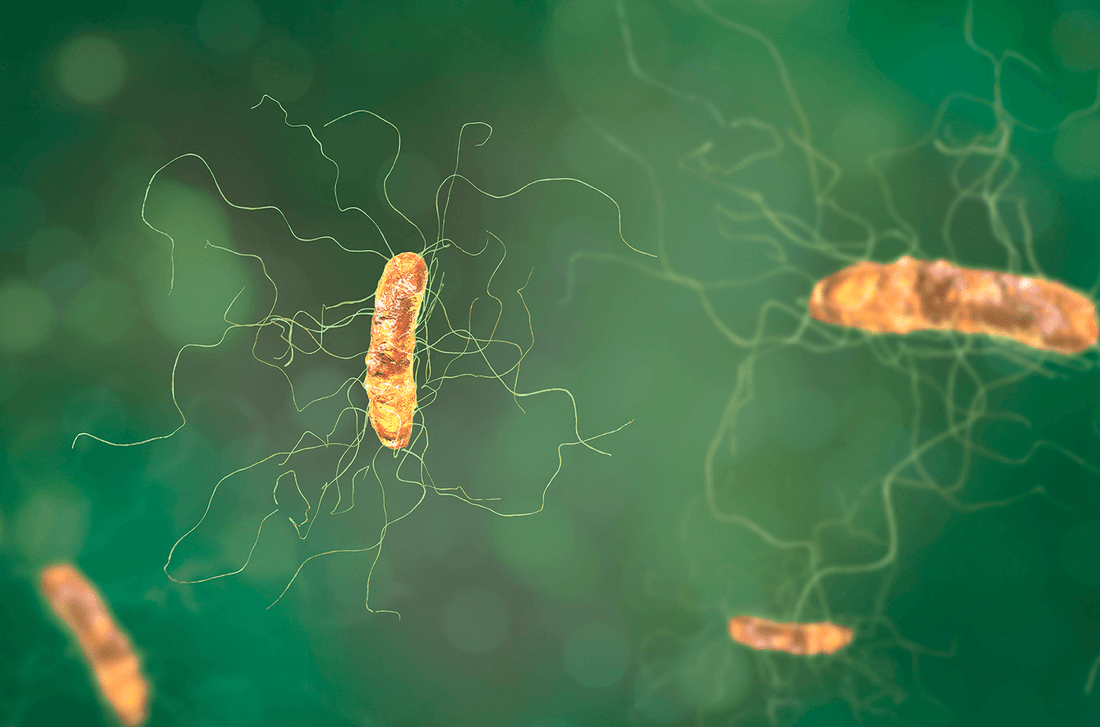

Superbugs. It’s a daunting title that evokes images of evil bacteria taking over the world. Well, maybe not quite so dramatic, but those who earn the moniker are usually deserving, particularly in the case of Clostridium difficile, or C.diff for short.

Clostridium difficile is a species of bacteria that can form spores; a hard biological ‘shell’ that makes it very resistant to usual methods of disinfection. A top priority for infectious disease care, C.diff has also acquired antibiotic resistance, meaning that many of our most potent defenses against this life-threatening infection no longer work.

While some strains of Clostridium difficile are benign in humans, there are strains of C.diff that release toxins that cause a serious inflammatory state in the human gut1-3. When these strains of C.diff infect the human gut, the result is watery diarrhea, inflammation and severe damage to the gut tissue as the infection progresses 1-3. If not properly treated, the infection can even result in death2.

Out of the hospital…and into the community

The spores that C.diff form make it difficult to sanitize in a hospital environment. These factors are why we once considered Clostridium difficile as solely a hospital-acquired infection that only the very young, very old and very fragile contracted. This thinking has now shifted as we have seen the infection affect the community and otherwise healthy adults1.

We contract C.diff via a fecal-oral route, meaning that we must ingest fecal bacteria to become infected1-3. Infection might happen if we touch surfaces contaminated with feces and then, touch our mouth.

Protect yourself against Clostridium difficile

Proper handwashing is our first line of defense against C.diff infection1. Our second line of defense, the acidic stomach environment, is ill-equipped to banish Clostridium difficile because spores are acid resistant1-3. Once ingested, spores of C.diff survive digestion to gain entry to your lower gut1,2. And this is where your third line of defense is key: a strong and healthy community of gut bacteria defend you against the growth of Clostridium difficile in your gut1-3.

To be clear, if you have a healthy microbiota, it is less likely that C.diff will cause infection2. When healthy, your community of good gut bacteria compete with potentially disease-causing microbes for space and food; they also release substances like short chain fatty acids, bacteriocins and hydrogen peroxide that help fight off these microbes directly.

The link between antibiotic use and C.diff

Antibiotic therapy alters both the size and diversity of the gut microbiota, which increases your susceptibility to infection3. Antibiotic use is strongly implicated in creating an environment hospitable for infection with Clostridium difficile. For this reason, every single time you take an antibiotic to fight infection, it is wise to take a probiotic. The Cochrane Collaborative has determined probiotics to be a safe and likely effective way to prevent C.diff infection resulting from antibiotic use5.

Bio-K+ is unique among probiotics in Canada, as it is the only probiotic to be Health Canada approved for both prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and C.diff-associated diarrhea when used with antibiotics. Clinical trials have shown Bio-K+ to protect the microbiota against the negative side effects of antibiotic use and actively fight C.diff infection6.

The three synergistic Lactobacillus strains in Bio-K+ help to fight off disease-causing microbes, help your community of bacteria bounce back and reduce the gas, bloating and diarrhea associated with infection and dysbiosis6.

But don’t antibiotics kill probiotics? Not if you use them properly. In the clinical trial, two capsules of Bio-K+ 50 billion capsules, taken during each day of the antibiotic treatment and for five days after, was shown to be the effective dosage to protect against C.diff and antibiotic-associated diarrhea.6 This is the equivalent CFU to two drinkable Bio-K+ bottles per day.

When do you take the Bio-K+? Two hours after one of your antibiotic doses; it is that two-hour window that allows the antibiotic to move through your system so that the Bio-K+ can bring it’s repopulating powers right behind. So don’t wait until antibiotics have diminished your intestinal flora- take Bio-K+ to resist the deleterious effects of antibiotic use to help you stay strong.

Bio-K+ has devoted decades of research to ensure the quality and efficacy of their formula; you can trust Bio-K+ as a safe and effective probiotic for your entire family.

Do you have any other questions about the health of your microbiota or C.diff bacteria? Ask us in comments below. If you are looking to stock up on Bio-K+, head to our store locator. For more information on Bio-K+, probiotics and digestive health, contact us, find us on Facebook and Instagram or join our community.

References

- Burke, Kristin E., and J. Thomas Lamont. “Clostridium Difficile Infection: A Worldwide Disease.” Gut and Liver 8.1 (2014): 1–6. PMC. Web. 31 Jan. 2018.

- Furuya-Kanamori, Luis et al. “Asymptomatic Clostridium Difficile Colonization: Epidemiology and Clinical Implications.” BMC Infectious Diseases15 (2015): 516. PMC. Web. 31 Jan. 2018.

- Britton, Robert A., and Vincent B. Young. “Role of the Intestinal Microbiota in Resistance to Colonization by Clostridium Difficle.” Gastroenterology146.6 (2014): 1547–1553. PMC. Web. 31 Jan. 2018.

- Horvat, Sabina, et al. "Evaluating the effect of Clostridium difficile conditioned medium on fecal microbiota community structure." Scientific reports7.1 (2017): 16448.

- Goldenberg, Joshua Z., et al. "Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea in adults and children." The Cochrane Library(2013).

- Gao, Xing Wang, et al. "Dose–response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophylaxis in adult patients." The American journal of gastroenterology105.7 (2010): 1636.